“So what if you’re ugly?”

I wore an honest face. It was an honest question. We were both uncomfortable.

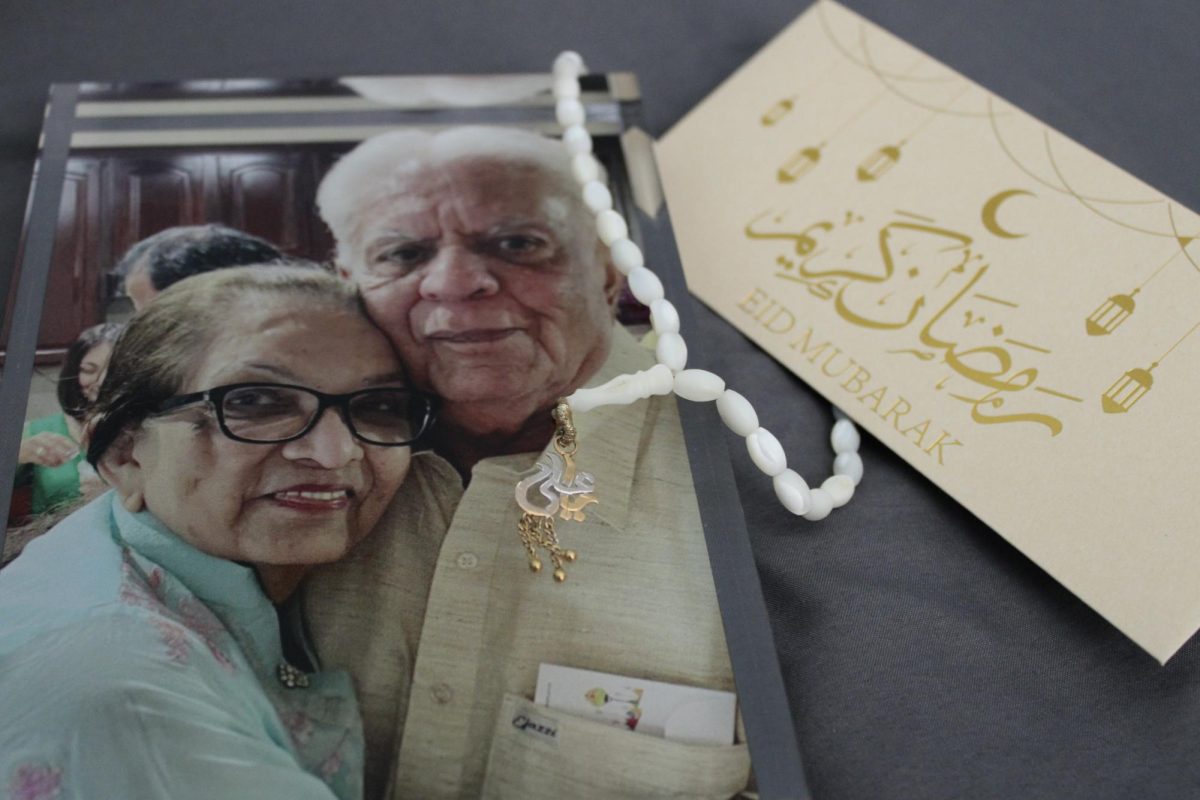

It was June, and summer’s inescapable humidity stuck to our skin, making the air thick. She asked me to show her photos I had of her, but by the third picture, she was already sighing heavily — complaining about everything she disliked about her face.

She waited for me to reassure her, but I stayed silent. I felt exhausted, always hearing everyone pick apart their appearance, including myself.

We both knew no words of mine could stop her disappointment when she looked at herself — not if she refused to believe it within, so I asked the question: so what if you’re ugly? So what if anyone is ugly? Why do we even care?

There are people just barely surviving.

Society’s hyperfixation on beauty distracts us from bigger problems. In today’s world, societal issues are complex and unpredictable. In order to feel the control people desire, they hyperfixate on what they can micro-control, which can lead to obsessions regarding weight, optimizing personal beauty and prioritizing appearance over character.

While grossly prevalent today, the obsession with beauty has been a major part of human history. By the 1920s, beauty had become a business in the U.S. with the Industrial Revolution leading more people away from rural areas and into cities of promised opportunity; people went from seeing tens of people a day to thousands.

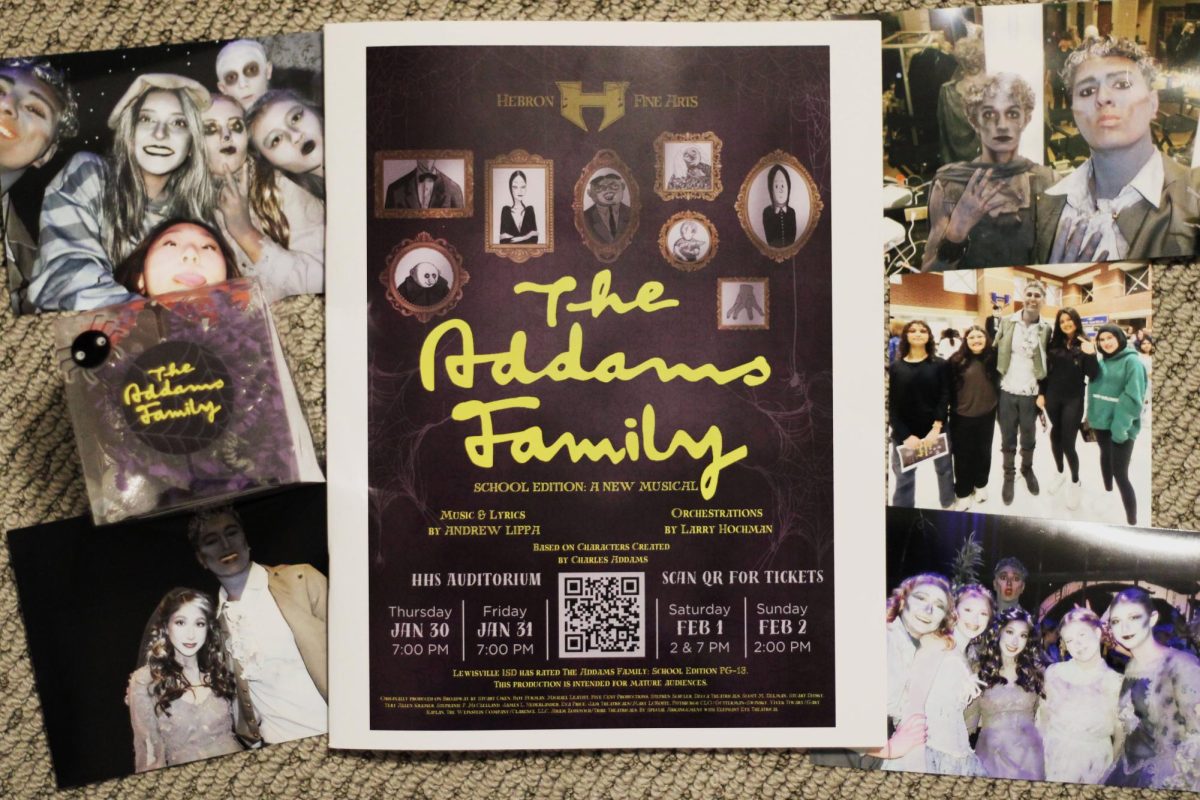

It was apparent to those wanting success that, in order to play the part, they had to look it; that was when the “working people” look was born. In order to stand out, be successful and market themself to society, people have to create personality through appearance.

Corporations began to profit off of this reality, causing a shift in marketing strategies that primarily targeted women. For soap companies, such as Palmolive, their soap did not only clean and disinfect, but made people’s skin “lucious” and “beautiful” — promising quick solutions using solely their product.

This tactic is still used today, especially by social media influencers with perceived success and beauty. They sell their “lifestyles” to those who are susceptible and as a result, some of my friends spend hundreds of dollars on makeup to cover up insecurities and younger kids believe they need anti-aging skincare.

It is a sad way that people live: body checking strangers at the grocery store, believing they lose merit as they age and believing the more one aligns with a constructed beauty standard, the more they deserve love, success and recognition. Artists are beautiful. Actors are beautiful. Everyone wants to be beautiful.

We have all been told in order to be accepted, we must be beautiful, but at its core, it’s a facade pushed by those who want us to be distracted.

People greedily overconsume, despite knowing millions of tons of clothing textiles are being dumped in oceans and neighboring countries every year. The beauty industry is a multi-billion dollar industry, only recently promoting “body positivity,” but still sells products promising to cover up “unwanted blemishes” and “imperfections.”

The first step to moving past the fixation on attractiveness is understanding what triggers the fixations: the deep-rooted idea that in order to be loved, one must be the standard of beauty. This is a marketing strategy and nothing more. We’ve been fed this illusion by companies who pushed a very specific beauty: white and thin. It may vary decade-to-decade, but it is, in the end, just a remake of the same model.

Whenever we find ourselves tearing each other down for our appearance, we must remember that being attractive has nothing to do with merit. It is not a competition, and people must notice what triggers them to spiral.

People need to stop thinking so much about themselves and instead think of others. A supportive community and inner circle has been proven to boost one’s overall self confidence by providing them with people who understand their struggles.

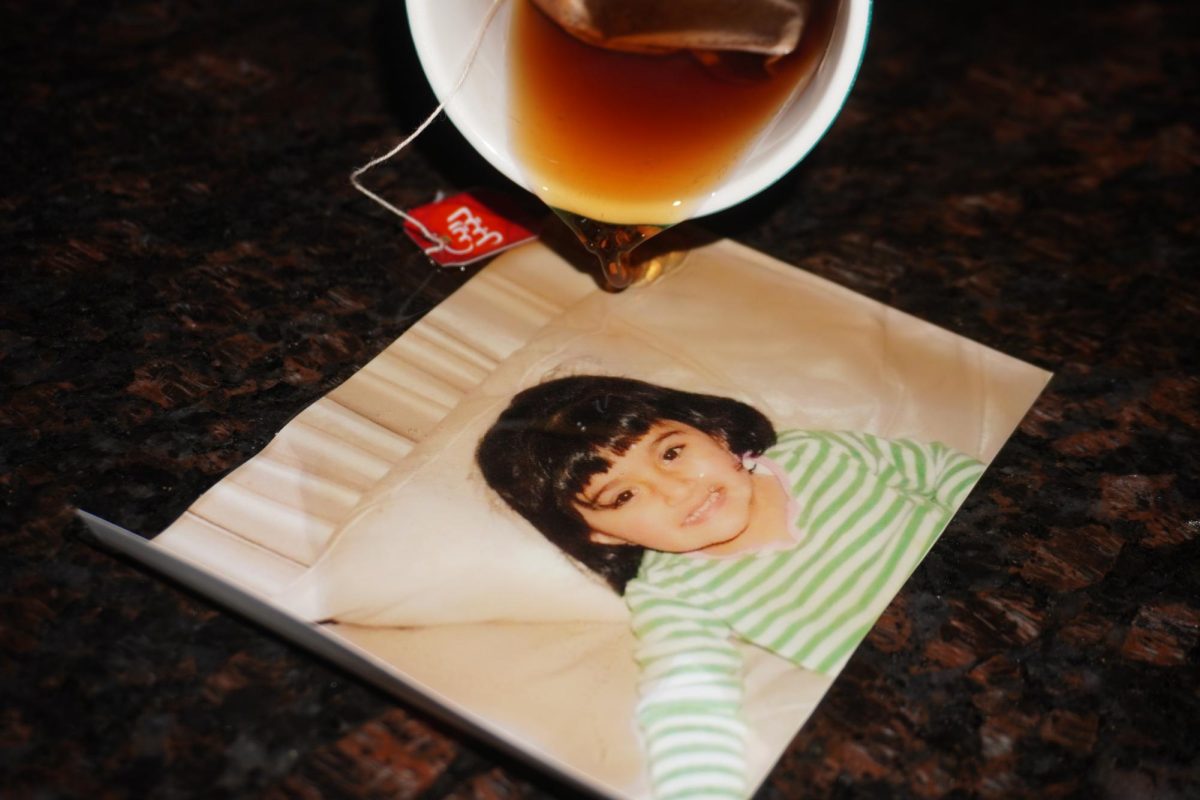

The next generation shouldn’t have to avoid swimming at pools because of body insecurity. Future generations of business owners shouldn’t have to worry about how they appear, but instead, be focused on how to better society with their skills.

I don’t want anyone to ask if they’re ugly; I want them to instead think, “So what if I’m ugly?”