Rows of chairs separated me from my mom’s body on the table.

Each passing second made me dizzy. The raw skin on my cheeks burned each time I wiped away my salty tears.

She was beautiful, but unrecognizable — heavy, strategically placed foundation attempted to cover every inch of death on her skin. I chose the blue, simple dress she was wearing, and the artwork I made weeks before her death rested on top of her still stomach. It felt like I was watching everything in third person.

The closest I got to my mom during the viewing was a few feet away. I wish this weren’t the case.

I wish a lot of things: I wish I had held her hand and kissed her forehead. I wish I would have taken a photo of the sunlight coming through the window that softly bounced off the hairs on her arm. I wish I could remember how it felt to be physically intertwined again, like we used to when we watched movies.

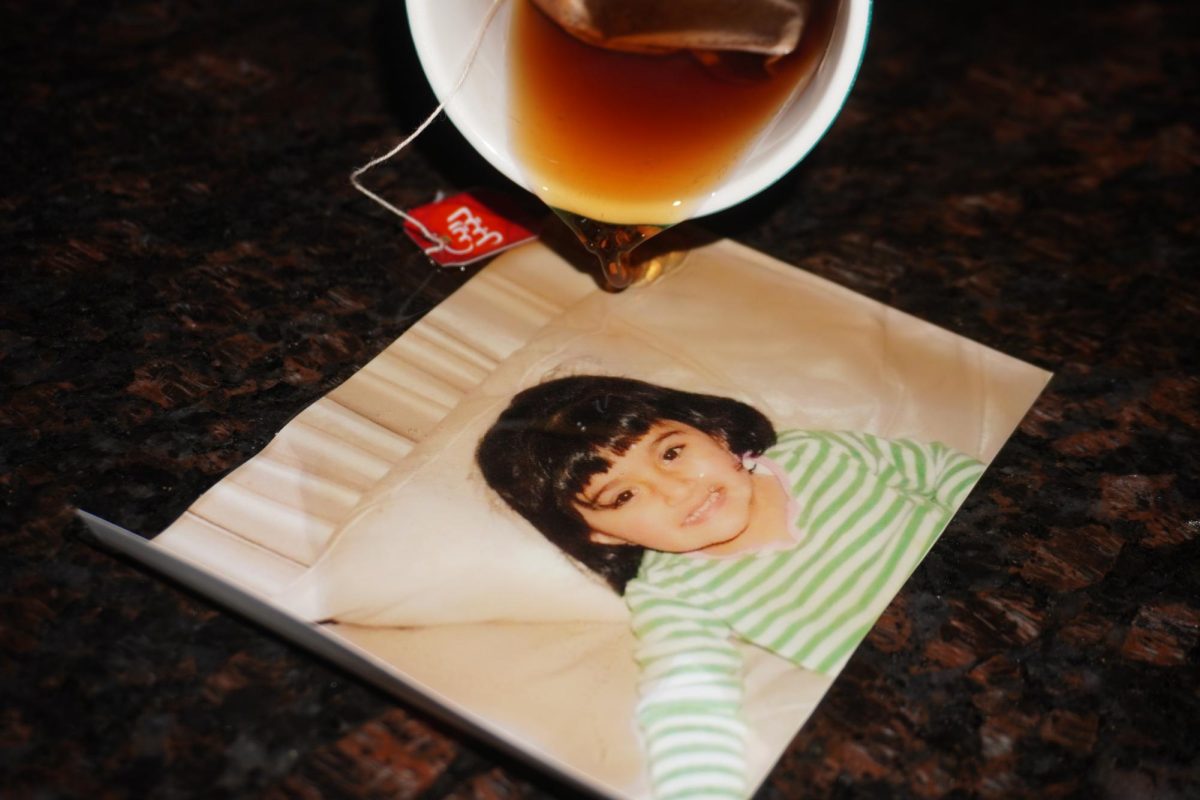

My mom passed away in 2020, when I was 11 years old, and the pandemic gave me an immense amount of solitude and time to reflect — something I avoided doing at all costs.

Her death was expected, but the way she died wasn’t. She was an addict, and in her last living years, she was homeless and not present in my life. Her death wasn’t because of an overdose, sickness, hunger or assault; she was killed by another little girl’s dad recklessly driving under the influence.

She was killed by someone struggling just like her, a human who has felt immense love, sadness and regret.

Despite my mom’s absence, I never felt angry at her. In my oldest memories, whether it was playing at the park or eating Oreos in front of the TV, I always felt loved, comfortable and seen.

I was put in programs to help kids who live with addicts, so I understood from a young age that her disappearance was never my fault. However, when I see a dandelion in spring or a kid holding their mother’s hand in the grocery store, I regret that I didn’t beg my family every day to find her and bring her home.

When I feel this way, logic doesn’t matter; all I wish is that I could hug her one last time and tell her I love her.

But I can regret all the things I didn’t do or I can accept that I was just a kid meeting the face of grief for the first time. There were things I couldn’t change, no matter how much I tried. I remind myself that she loved me, and I know that deeply. All I can do now is hope she knew I loved her, too.

The most important thing I learned from my regret-related grief is that I need to feel everything — no matter what. Every pain in my heart and ache in my bones is an expression of my love for her. It isn’t easy, especially when a wave of grief hits me at school or when walking down the street, but with time, it becomes more tamable and beautiful. With each passing autumn and spring, I see her more and more in the little things and feel more alive in my love for her again.