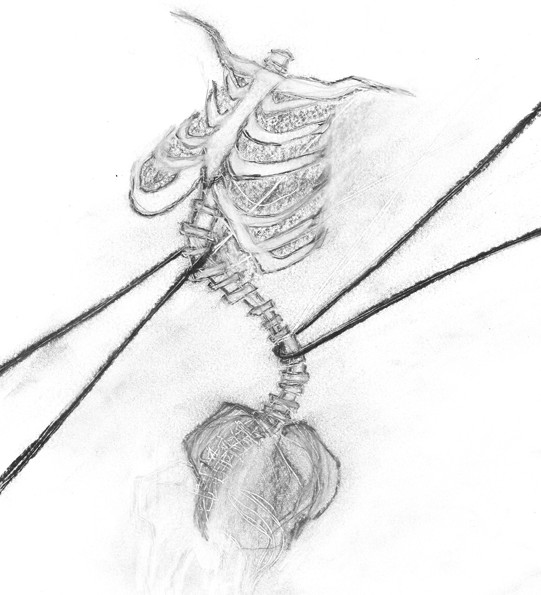

Twisted spine

March 19, 2015

A cluster of kids about my age walked by wearing navy and cream colored uniforms, knee-high stockings and glossy shoes. The Madelines, as I referred to them. All smiling, joking around with each other. I guessed they were here on some kind of school field trip. I watched them from an iron table where I sat between my parents. Kicking my feet over the linoleum, eating from a bag of white cheddar popcorn, I watched them unabashedly, glaring from under my unbrushed hair. I caught one of their eyes, and they looked away.

This was my second time to a children’s hospital in Dallas. I was here to get treatment for what had been diagnosed about a month previously. After x-rays and a fair amount of probing and prodding, I was informed that I had scoliosis, a condition in which the spine grows at an abnormal curvature. I already knew that, my mother noticed it on me when I was eight or nine. It wasn’t any big deal, lots of people have scoliosis, about 5 percent of the population, but only about .2 percent require treatment, and I got caught somewhere between the decimal and the two. I had already been measured for a back brace and here I was, at ten years old, to pick it up.

In the consultation rooms, they displayed my x-rays on swivel desktop screens and point with pencils.“This curve is at 42 degrees. This one is 15.”

I learned that there are different kinds of curves, usually S or C. Mine was an S, meaning there were two curves in two different spots. I learned that if the curve passed 50 degrees there would be serious consideration for surgery, a last resort solution. This was going to keep that from happening.

“You’re lucky you didn’t have to wear one of these a few years ago when they went up your neck,” the doctor said as he brought the brace out.

I didn’t say anything. I had nothing to say to that. I didn’t even know what I thought, I just felt white hot anger and it made everything harder to see.

They gave me these grey ribbed undershirts to wear under the brace that reached up past my armpits. The fabric clung to me like a second layer of skin, thick and grey. The doctor stretched the brace open with strong hands and when he let go it snapped around me. He fed the velcro through the buckles and pulled hard. A breath fell from my mouth. He buckled the next two straps, each pull compressing me tighter, pushing my shoulders and lower back forward and closing my ribcage. I kind of expected it to just fit over my body, but obviously I hadn’t thought this process through. The brace was literally conforming me to grow the right way, to suppress further damage. It’s job was to straighten me out. It hurt the top of my skin, but it also hurt me from the inside. My bones and muscles ached as if bruised.

“Why don’t you walk around some and come back before you leave,” he suggested.

I pulled a shirt over my head and looked sideways at my reflection.

“Sure.”

So we walked through the multi-colored hallways and outside. I walked along the sidewalk of the hospital entrance, one foot in front of the other, feeling like I was on a tightrope. My whole center of gravity had shifted. I felt twenty pounds heavier. I was trapped in an upright position, unable to stray from the grip it had on me. There was a large hole on the left side of the brace so I could breath. My left rib cage protruded from it, my body and bones spilling out of its hold awkwardly.

I went to the playground, touched the copper statues in the garden and looked at the jungle gym but didn’t climb it.

That summer my family and I took a road trip to Wyoming. While our car was pulled over at a rest stop, I took the opportunity to take a break from my brace, especially eager to distance myself from the spots where it chafed against me. I wedged my torso from its grasp. Exhaled. From underneath my shirt I peeled off the undershirt, stuck to me in a coat of sweat. I touched the spots under my arms that stung. Blood stuck on my fingers. I rubbed it off on my legs and tried to get the air, hot and heavy, over the bare skin before I had to put the brace back on. If I was a boy I would’ve just taken off my shirt, but girls don’t do that, do they? And then it was time to put it back on.

I ignored the way it felt like a pin being pushed into me.

After a while I built up callouses. There were these rough spots on my sides, under my arms; my own armor. I would rub on alcohol to speed up the process.

What you have to do when something like this happens to you, is adapt. You have to figure out how to live, with this very evident thing, this thing you can’t walk away from, even if no one else can see it.

Needless to say: summers were the worst. As soon as I stepped into the sun I started to sweat, and it clung to me even after I was in the air conditioning and the perspiration evaporated off of everyone else. I spent them mostly indoors, mostly in my bedroom with the fan whirring above head. I read a lot, mostly fiction, mostly Harry Potter. And shut away after several consecutive summers, I became very pale.

Sometimes when I dressed in the morning, I would imagine I was a secret agent, strapping on my bullet proof armor. I’d even fantasize about getting attacked with knives.

“Ha!” I’d exclaim as the blades bounced off of me. What a silly twist of fate that would be! It never happened, but it was something to think about.

In general my treatment wasn’t exactly a secret, but I treated it like one. I liked to be selective about who I told. I don’t know how many in total knew, and I would bet that there were a few who figured it out or saw and just never mentioned it. Everyone who did find out was exceptionally sweet about it. No one ever talked about it except to offer help. After growing up I see now that I didn’t have to keep it so classified. In fact, it might have been better had I been more open about it. I was afraid of not being looked at as the same, or of being set at a lower standard. Inevitably, there were times when someone would knock into me. The questions were embarrassing.

“What is that?”

“What do you have under your shirt, a book?”

My face would get hot as my heart rapped against the plastic. “No!”

And I’d leave it at that.

There wasn’t a whole lot I couldn’t do, but if I ever did need help everyone was always ready to assist.

Regardless, I became a little bitter. Especially when classmates would don ankle boots or wrist braces for a couple of weeks and receive sympathy. Any time someone complained about discomfort I would quietly seethe. One night, in a fit of absolute frustration, I chucked my brace at my bedroom window. I felt good, but there was still a moment of panic before it clattered against the glass and down the wall when I really hoped it hadn’t broken. Still, I knew that I hadn’t thrown it as hard as I had wanted to. I could’ve given more.

I could never move to the extent I wanted. Even my freak outs had restrictions.

I wasn’t exactly sick, but I was in a constant state of treatment. Everything was going to be okay granted I did what I was supposed to. Or so they told me. And so there I was stuck. Somewhere between movement and paralysis, between healthy and sick, and between sympathy and indifference.

Doctors had told me that this whole process would be over somewhere mid high school. As a fifth grader that seemed substantially far off, and I started to romanticize the idea of what my life would be like when I didn’t have to wear it anymore. I imagined a future version of myself, with a small waist in fitted sundresses, the light cotton over my skin. I imagined a life where I could run again, feel the air fill up my lungs without restriction. I imagined a lot of things, the things I would be able to do and wear. The shedding of an exoskeleton. A me who could move however she wanted. I imagined sunshine.

The summer before ninth grade, at a normal checkup, they told me I could take off my brace and never put it back on. My brain sort of malfunctioned. This news was completely out of the blue. I thought I had maybe one or two more years to go. I’d always known I would cry, but I didn’t expect the way that news made me feel. It was like being hit really hard by something really heavy. I didn’t even feel relief. I just felt. It overwhelmed me completely.

“Well give your dad a hug!” the doctor said.

I wrapped an arm around his shoulders robotically. This wasn’t really about my dad. This was about me.

I walked out of the hospital with the brace in my hands. I tried to not cry and failed. I noticed people looking at me, probably figuring the worst, I mean, we were in a hospital. I didn’t want them to think that. This was supposed to be happy.

When we got in the car I lost control. I sobbed, heavy sobs that shook my whole body.

I had worn my brace for four years. That was a third of my life. When I had my brace I knew exactly who I was. When it was taken away I didn’t really know who that was anymore.

I couldn’t sleep that night. I dreamed of waking up distorted, shoulders hunched like a picasso painting, and not being able to right myself. I hadn’t gone a night without it since the day I got it. I obviously didn’t like wearing it, but my parents had engrained the idea in my head that if I didn’t, this would all be for nothing. Bad things would happen. The second night I wore the brace to sleep even though I didn’t have to. I had nightmares. This was all exceptionally ironic considering I had spent so many mornings wishing I could wake up in my own skin. After that second night it was gone for good.

Every day before I could stop wearing the brace was pretty similar. The first thing I’d do when I woke up was take off the brace, set it on the floor and lay back down. I’d feel the sheets against me, my weight against the mattress and take a big breath, my ribcage filling with air, growing, opening up and out. I’d hold my breath, let the air swirl around inside my chest, then let it slip through my lips like a ribbon.

After a while you get used to the way your life is. You don’t forget how it used to be exactly, you just forget how good your current situation would feel to past you. But when I’m studying with my spotify running in the background, and I get frustrated and overwhelmed, and that one song comes on, I can get up and jump around and shake my hips and flail my arms and twist and roll and I know that if I had never had to wear my back brace, I wouldn’t be so grateful.

Big time fan • May 26, 2015 at 11:31 PM

Only a gifted writer could express so powerfully feelings that the rest of us will never truly know but can better understand because of your talent as writer.

Kathy Lancaster • Mar 23, 2015 at 8:22 AM

Caryn, I admire your courage in sharing, informing, and writing with such honesty and clarity. This piece has served and supported children and families who experience fear, uncertainty, and pain with little acknowledgement or understanding from those around them. And, it has allowed us a view of a world that is unknown to 99.8 percent of us. Whatever careers await you, I hope you will continue to educate with your exceptional writing skill and talent.