Undocumented

Junior shares story of crossing the border

March 13, 2020

Editor’s note: To help protect her identity, the pseudonym “Lin” is used to refer to the main source in this story.

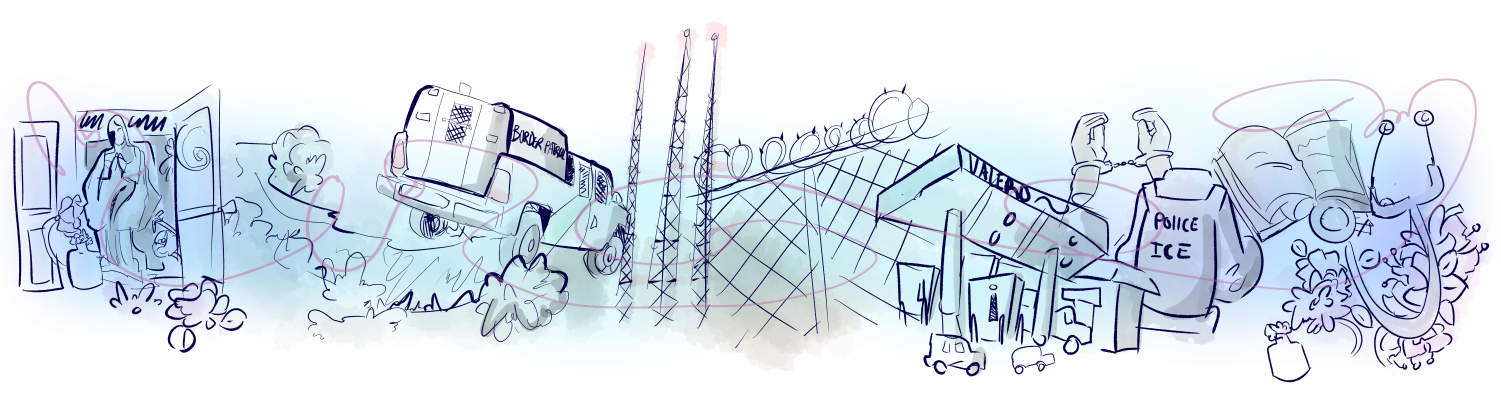

They had minutes to cross before border patrol would be back.

11-year-old Lin and her mom ran toward the chain link fence that seemed to tower over them and began climbing.

As they reached the top, Lin’s pants got caught on the coil of barbed wire capping the fence. As she struggled to free herself, she spotted a trailer approaching. Lin’s heart began pounding. She did not want to be the reason they were caught.

Her mom worked to untangle her from the wire, only to have her finger get snagged in the wire too. Moments later, they were back on the ground. They had fallen to the other side.

Lin’s mom had a gash running down her middle finger.

She was hurt, but Lin knew they could not stay idle on the ground. The guide told them if they stayed near the fence for too long, border patrol would be there before they knew it.

“I grabbed the backpack, and I grabbed my mom and was like, ‘Come on mommy, we can’t stay here,’” Lin said. “My mom looked at me, and she got up like nothing happened to her.”

Lin poses for a photo.

Lin, now a junior, and her mom are undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. from Mexico City with hopes of securing employment and safety. Lin’s mom decided to migrate because of what happened to their nextdoor neighbors: gang members broke in and beat some of the family. Nobody was killed, but the next day, she told Lin they were going to visit family they had not seen in a long time.

“She didn’t want to scare me,” Lin said. “She told me it was more like a journey than a dangerous thing, so I wouldn’t be scared. I was sad because I didn’t get to say bye to [any] of my friends.”

Before they left, Lin lived in a two story home on calle la Merced Colonia with her mom, uncle, grandmother and brothers. The houses on her street were very close to each other, and in front of Lin’s house was a celebrated statue of Mary the neighbors decorated with flowers. While the neighborhood was riddled with crime and drugs, religion was prevalent, especially for Lin’s family.

Lin typically went to school from 8:20 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. The school was blue and three stories with a courtyard in the center. She was a diligent student.

From school, her mom would pick her up, and together they would walk to her mom’s store in the market, where they would spend the rest of their day. At the market, there was a bit of everything, from clothes to produce to flowers.

Lin’s grandmother took over her mom’s store, where she sold decorations for events, after they left for the U.S.

“We have family here [in the U.S.], and one of my uncles asked me if I wanted to come live over here,” Lin’s mom said (translated by Lin). “I was brave enough to say yes even though there were a lot of risks. I could lose my life on the way here.”

Lin and her mom traveled to the Mexican border city of Nuevo Laredo and stayed at a hotel under the supervision of coyotes – people who smuggle migrants across the border.

Lin and her mom were instructed by the coyotes to meet at a certain time and place to attempt to cross the border into Laredo, Texas.

For six days, Lin and her mom met at the banks of the Rio Grande with individuals from various countries with the same goal. Each day, they would have to turn back to avoid the border patrol. They were caught the seventh time they tried to cross.

____________________________________________________________

Lin was soaking wet. They used rubber tires as makeshift boats to cross the river, laying on top of them as others dragged the tires through the water. There were only four tires, so it was women and children only, while the men, even if they did not know how to swim, would tread through the water.

“We saw a dead body on the side of the [river],” Lin said. “I was little. They called him a stick, so I wouldn’t get scared, and they just told me to turn around, but I did see it.”

The coyote told them once they crossed, a truck would be waiting for them in a Laredo neighborhood about a mile away. With a stick, he drew a makeshift map on the ground, showing the group where to run once they were past the foliage on the other side of the river. The coyote would not be running with them, so they were on their own.

Most of the group, including Lin and her mom, only made it halfway before they were spotted and stopped by border patrol.

“It was obvious because it was an open space, and so you can see a person walking from far away,” Lin said. “Everyone was running, and there was only one guy that got to the truck.”

Lin and her mom were ushered into the back of a white truck by border patrol. Lin did not know what to feel. She was just glad she was with her mom.

They found themselves among several strangers in a frigid white room with a cement floor. They had been taken to a detention center in San Antonio.

“There was this other lady from the group who was trying to take me,” Lin said. “Because people who enter the USA with kids, they give them less days in the immigration center, well, back in the time.”

Because of its diversity, the group, consisting of Guatemalan, Salvadoran and Hondurian people, that crossed together was separated into different rooms. Other than Lin and her mom, only one woman and her two children were Mexican.

On one side of the room was a large window looking out to the rest of the detention center so border patrol could keep an eye on them. Lin was given food, but her mom was not, and at night, they were given a foil sheet for warmth. They were not allowed to call anyone.

Lin and her mom were released from the detention center and taken back to the border the next day. The officers let Lin’s mom off with a warning: if she tried to cross again, they would detain her for months and separate her from Lin. Lin began to cry. She wanted to go back to her grandmother’s. She did not want her mom to be taken away from her.

Just like they had almost every day of their journey, Lin and her mom called Lin’s godparents, who lived in the U.S., to assure them they were OK.

“That’s when the whole kidnapping topic came up because the [coyotes told my godparents while we were in the immigration center] that we were kidnapped, and they were asking for money,” Lin said.

Lin’s godparents were skeptical about the coyote’s claims of Lin and her mom’s kidnapping and demanded proof. The coyote hung up. Once Lin’s godparents received the call from Lin’s mom, they told them to leave everything and avoid going back to the hotel being watched by the coyotes. There was a possibility that kidnapping could become a reality.

“Of course my mom was scared,” Lin said “She looked pale. Oh my God she looked pale, and I got scared, too. And then she was like, ‘Don’t ask anything. Just walk.’”

Lin and her mom stayed at another hotel before leaving for Piedras Negras, another border city northwest of Nuevo Laredo, the following morning.

“I was little, and I wanted to go back home, and my mom was like, ‘Just one last try, and if it doesn’t work, then we go back home,’” Lin said. “The last try we went through Piedras Negras, and we actually made it.”

____________________________________________________________

Lin and her mom stayed at her godmother’s sister’s house for about a week in Piedras Negras. On the last day of their stay, they attended a prayer at someone’s house. The next morning, Lin and her mom boarded a bus with another coyote and group which took them to the Rio Grande.

From the Rio Grande, Lin and her mom would spend three days and two nights walking through remote and rural grassland. At some point, three broadcast towers adorned with red lights blinked in the distance. The coyote told them once they passed the last one, they would be at their destination.

“I kept looking at the red light,” Lin said. “Whenever I thought we were close, it was so far away. Even if we walked miles, we weren’t close to it.”

A white Ford Expedition was waiting for them sometime after they passed the broadcast tower. The coyote told them to hurry into the truck.

Most of the men in the group were packed into the tail of the car and covered with a tarp. Lin’s mom was curled up under the glove compartment on the passenger’s side. Lin was stacked on top of other people laying on the floor of the backseat.

Lin and her mom were taken to a house in Austin. The house was small: two bedrooms and one bathroom, with 18-20 other immigrants crowded in the living room. The coyotes told them to recuperate at the house, but Lin’s mom was not ready to rest until she was with her family. It was about 3 a.m. when Lin’s godparents received a call. Her godparents immediately began the three-hour drive from Dallas to Austin.

At around 7 a.m., the coyotes drove Lin and her mom to a Valero gas station. Before they could get out, the coyote locked Lin and her mom in the car. He then met with Lin’s godfather and demanded $200 more for each of them.

“[It was] like we were some kind of toy,” Lin said.

Lin’s godfather handed over the money, and Lin and her mom were let out.

Lin and her mom were taken to her godparents’ house. From there, Lin’s uncles picked them up. Lin’s mom was not faring well; her legs were swollen and her nails began to fall off. The cut on her hand was still open and needed treatment.

“My mom couldn’t walk,” Lin said. “That’s how hurt she was.”

One of Lin’s family members received a call the next day from an unknown number. The caller asked if Lin and her mom were OK. They said everyone else in the Austin house was arrested by ICE.

____________________________________________________________

Lin started school on October 18, 2013, about three weeks after they came to the U.S. Despite being a sixth grader at her old school in Mexico, she was held back to fifth grade in order to learn English. None of the staff spoke Spanish. After a week or two, the kids who did speak Spanish were tired of translating.

“With them holding me back in fifth grade, [it] helped me because I know that if I didn’t learn English here, I wasn’t going to be successful, and that’s just how it is,” Lin said.

Lin poses for her first day of fifth grade in the U.S.

Lin’s mom wanted to be closer to her family, so they moved in with an uncle. Lin transferred schools for the second semester to attend a school with bilingual classes.

Lin’s stay in the U.S. has gone smoothly since then; she improved in English and focused on school.

“I feel like I’m successful with the simple fact of just being here,” Lin said. “I have greater opportunities that I didn’t have in Mexico.”

In June 2019, Lin consulted with a law firm and was told to go to immigration court to appeal for residency before she turns 18. Lin never went. With current administration tightening immigration laws, the high cost of a good lawyer, and the small window of time before she becomes an adult, Lin has not been able to move forward and become legal.

“That is one of the hard parts of being here,” Lin’s mom said. “Everything is a risk.”

Lin and her mom try to be careful and avoid places where deportations are common. They currently do not have any protection from immigration.

“There’s all the chances that I could get deported, because I don’t have anything to protect me,” Lin said. “I don’t have a work visa. I don’t have anything.”

Lin wants to go into the medical field, but her undocumented status is detrimental to her desire for career and higher education.

One of the reasons Lin is interested in the field is that if she gets deported or cannot attend higher education, she can still study medicine in Mexico. Lin plans to spend her senior year taking dual credit and AP classes, as well as career center courses to prepare for college and help out her mom with the cost.

“I know I came here with a purpose, and I’m not going to waste that purpose causing myself more problems than [the ones] I already have,” Lin said. “If I came here, it’s to be better for myself and my family. I know where I’m going, but I never forget where I come from.”