Lifelong roller coaster

Junior with Autism overcomes challenges to take general education classes

November 13, 2017

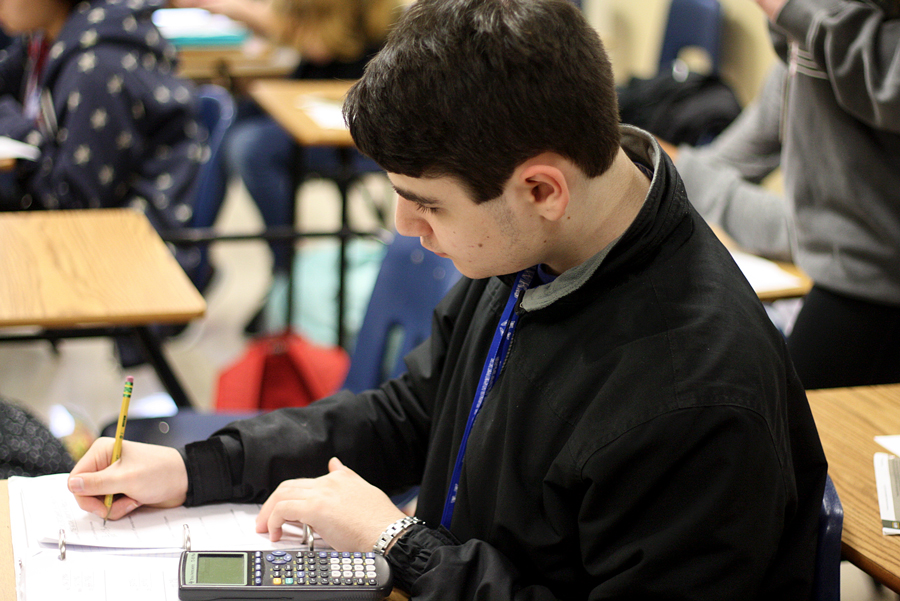

Junior Elliott Saltar has Autism: Asperger Syndrome, to be exact.

Diagnosed with Asperger’s, a developmental disorder affecting communication and ability to interact socially, in 2007, Elliott has faced and overcome challenges throughout his life. Elliott takes all general education classes and has learned to deal with both Asperger’s and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

“I like general education more,” Elliott said. “I mean sometimes I get kind of out of whack, but I tend to learn better in general education classes rather than special education because I have specialized teachers who understand what they’re teaching more as opposed to sitting me in front of an online program and hoping that I learn something.”

Elliot’s move from the special education classroom to the general education classroom is just the latest example of his tendency to exceed expectations, despite the obstacles he’s faced. For example, his ongoing passion for technology began when he was three and he received his first computer.

“I was still in my play pen and using a computer,” Elliott said. “Anything with a computer, I’m drawn to like a magnet. I’ve been using computers since I was really little. I think it’s sort of an addiction, honestly.”

And when he was four, he taught himself to read.

“I remember [we were] flipping through satellite TV for a show to watch,” Elliott’s father, Michael Saltar said. “I wasn’t really paying attention to it, scrolling through the menu and I just paused for a second on the channel saying The Oprah Winfrey Show, and [Elliot] looked at it and went, ‘No, not Oprah!’ And I’m like, ‘What? How did you know what it said?’ I didn’t even know he could read, much less understand what the show was even about.”

Elliott’s parents began to suspect something was wrong when he was in preschool. As a child, Elliott showed early and common symptoms of Autism, such as lining his toys up and organizing them rather than playing, banging his head against a chair and stimming, which is a repetitive self-stimulating behavior.

“At that age, [doctors] don’t even try to diagnose it,” Michael said. “They called it something else. Some kind of developmental disorder.”

Michael said he prefers to treat Autism as an injury rather than a disorder, and believes it can be reversed, although the process is difficult. Treatments are too experimental for insurance to cover, drug manufacturers are protected from being sued and treating Autism is expensive for the average person. With what treatments they could try, Michael feels that they have helped Elliott.

“I’ve kind of just given up on it,” Michael said. “It’s a lot of work [and] a lot of money. I’ve said basically, ‘Elliott, you take the reins from here. If you feel like you want to improve, if you want to go through some treatments yourself, go ahead. You’re bright enough. You know what to do.’”

But when Elliott was in second grade, something happened: mercury poisoning.

The maintenance crew happened to be changing the fluorescent light tubes in the hallway ceiling, and placed them near Elliot’s classroom. An accident occurred, and they fell over, shattering. Fluorescent light tubes contain a small amount of mercury, which diffused into the air.

Elliott and one other student in his class were directly affected by the mercury in the air. His family noticed a significant change in Elliot as a result of the toxicity in his brain.

“He lost his ability to do basic things like speak,” Michael said. “It was awful.”

Elliott stopped talking for six weeks. He became, as Michael puts it, “profoundly autistic.” They did not know if his voice would ever come back. After treatments and therapy including salt baths and ingestion of natural herbs, their prayers were answered.

“I remember the day he started using his words again,” Michael said. “And it didn’t come back little by little, it came back in a flood. It just made his mother and I cry tears of joy when that happened.”

From his time at Homestead Elementary to high school, Elliott had been in special education classes. Elliott was able to gradually work his way out of BIC (Behavior Intervention Classroom) by the end of freshman year.

“We have kids that work their way out [of the class] all the time, and that’s the goal,” BIC teacher Yanique Isom said. “We don’t want to keep them there because it’s not realistic to be in a classroom all day with five or six kids.”

During the beginning of freshman year, Elliott was in BIC full-time because he was severely OCD and would experience getting stuck.

“He physically couldn’t move because he was trying to get his brain to play back [something] over again,” Isom said. “It was pretty much an OCD problem. You couldn’t interrupt him when he talked, and he would make this noise trying to get himself unstuck. And it would cause a lot of emotion for him.”

Isom and Elliott were able to find the trigger for getting stuck, which was a lack of sleep.

“When I feel I get interrupted by someone, I just kind of like lock up,” Elliott said. “And don’t want anyone to pay attention to me whatsoever [when I get stuck].”

Once Elliott was able to control the issue and communicate with his peers and teachers about getting stuck, they knew he was ready to leave the special education setting. Elliott said his OCD probably has a correlation with Asperger’s.

“He’s very intelligent,” Isom said. “[And] very smart, so academically, he didn’t need us at all. It was just a matter of maturing and working through those issues that he had. He’s really come a long, long way and his story is truly awesome.”

Since the beginning of sophomore year, Elliott has been taking only general education classes and has an aide check on him for 15 minutes a week. He also has speech therapy every week.

“My [high school] experience has been rather nice,” Elliott said. “It isn’t like all the teen drama Disney Channel made it out to be but it feels a little bit more open. Although [high school is harder] and the school hours are also longer.”

Elliott has known about his Asperger’s for as long as he can remember; however, he did not understand exactly what it meant until he was older

“We rarely uttered the word ‘autistic’ to him,” Michael said. “We did say ‘Asperger’s’ instead since it sounded less threatening. When he was old enough to know the full story, I told him the full story. I told him everyone has a challenge to overcome, and so [Asperger’s] happens to be [his] challenge.”

Elliott feels that the Autism label hasn’t really had too much of an impact on him; however, he would dislike if someone put him on an unequal level because of it.

“I’ve had this problem with the Autism stigma,” Elliott said. “I don’t just want to be that weird kid, but people seem to be indifferent about it, so honestly, I don’t really care about the label anymore.”

Many people have helped Elliott along the way, including his parents and special educational teachers.

“I just want to say thank you to everyone who helped me along the way with Autism and special education,” Elliott said. “Even if I didn’t mention them in this interview, I’m sure they’ve done a lot to help me get where I am now.”